Neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s ability to adapt throughout life in response to experience.

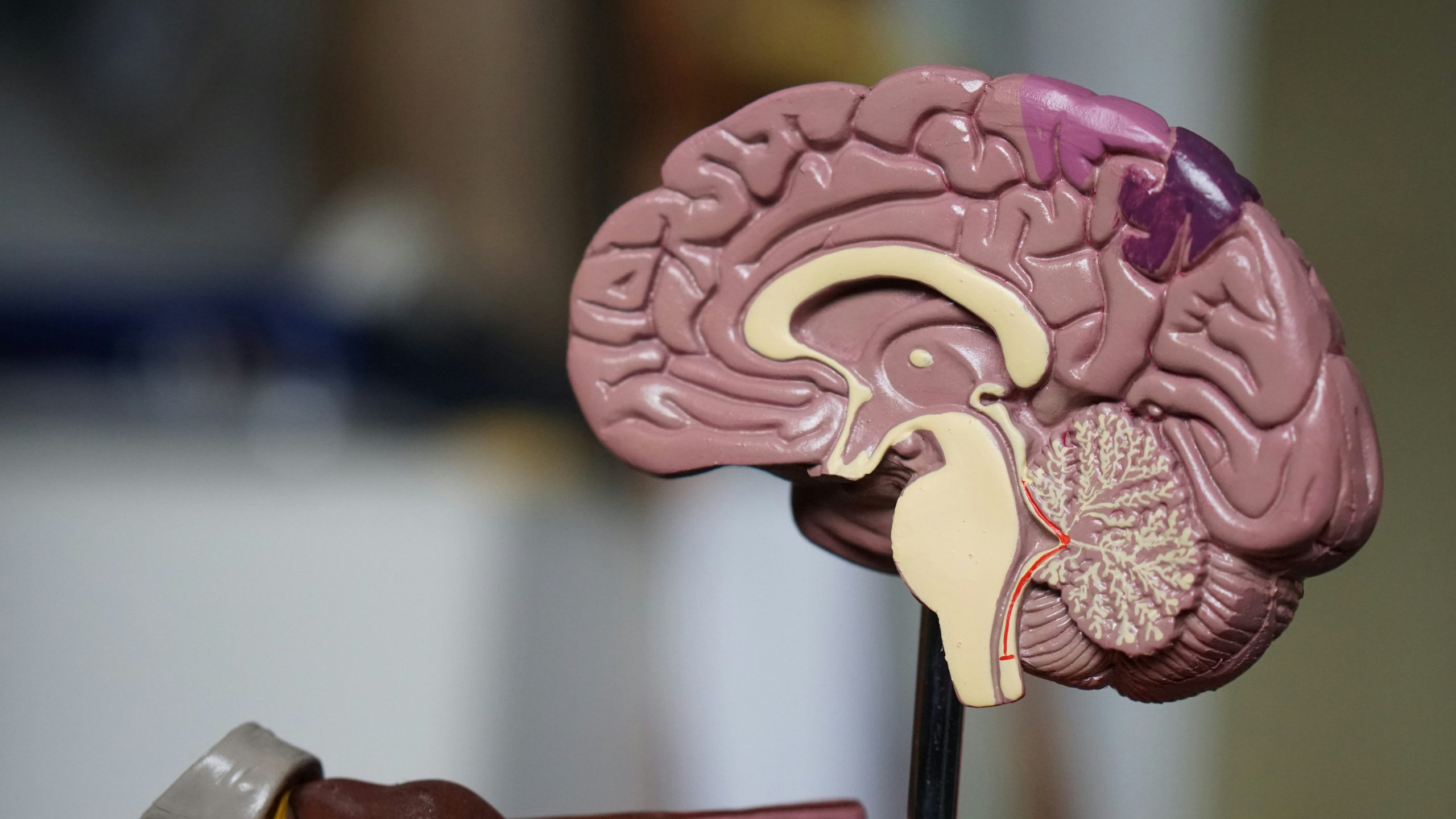

Your brain might demonstrate neuroplasticity when navigating around your town or learning a new language. In other words, the brain can be viewed as ‘plastic’ and is most flexible early in life; at birth you have 100 billion brain cells with few connections between these cells.

Research into neuroplasticity is even more important when helping people recover after trauma. Examples of physical trauma include brain damage from incidents such as a motorbike accident or surviving an accident where an iron rod penetrates the skull like in the case of Phineas Gage. Alternatively, psychological trauma can refer to incidents like violence, sexual assault and loss.

So how does neuroplasticity help people with trauma?

There are successful interventions for people with physical and psychological trauma due to research into neuroplasticity. Studies have shown that rehabilitative functioning such as developing a routine and aiding memory with cues has helped patients with physical trauma. For example, if a patient has suffered damage to their cerebral cortex from a bullet, rehabilitative functioning could help the brain to find new neural networks by learning in a different way to before the trauma. Similarly, bilateral stimulation can help patients reprocess their trauma or triggers when suffering from psychological trauma.

The aftershave of a man who sexually assaulted a woman may trigger a panic response every time she smells it, even though she knows lots of men may wear the same scent. An example of bilateral stimulation is eye movement processing which increases neural connections rather than isolating the incident to one part of a neural network. The person may feel less of a panic response to the aftershave due to the activation of neural connections.

Although the interventions provide support for both the evidence of plasticity and recovery after trauma, there are individual variations. As mentioned previously, the brain is more ‘plastic’ earlier in life and is more likely to adapt and form new neural connections than an adult brain.

This is normally the case where trauma is physical rather than relational-based. Genes also affect brain plasticity as individuals with polymorphisms (genetic variation) have lower neuroplasticity. They will require different interventions to achieve results similar to an individual without this gene. Education levels also impact neuroplasticity; someone with more access to education or a higher IQ will likely recover more quickly from trauma as their brain is more ‘plastic’.

Therefore, interventions will vary in success depending on a variety of factors such as age, gender, genetics, environment and the localisation of brain injury.

Future research could focus on how different interventions are needed depending on the individual in relation to neuroplasticity after trauma.