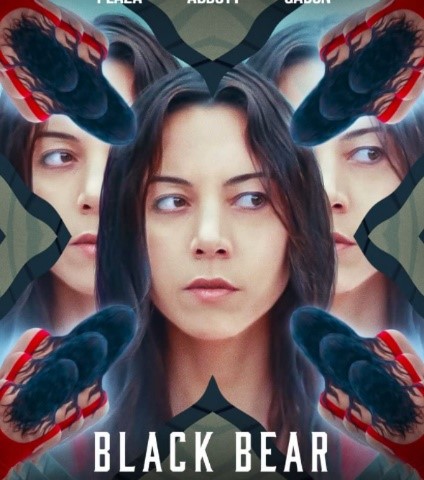

In a film possessing elements of horror, psychological thriller and dark comedy, it’s clear that writer and director Lawrence Michael Levine was aiming for the unconventional. With his new feature, Black Bear (2020), that is exactly what the audience gets- a film that revels in its hard-to-pin tone and twisting narrative.

Separated into two parts, the film centers on Allison (Aubrey Plaza), a director who visits a retreat in order to overcome her writer’s block. Allison stays with the retreat owners, Gabe (Christopher Abbott) and his pregnant girlfriend (Sarah Gaddon). In a wonderfully toe-curling opening, the on-screen couple bicker in front of an uncomfortable Allison – who is also just as happy to dig her claws in and stir the pot.

In an unnerving introduction told from the perspective of our third-wheel protagonist, we are a fly on the wall, witnessing the uncomfortable atmosphere of an obnoxious couple’s relationship breakdown. As the narrative progresses, the weirdness only thrives, and it isn’t until the second part that the head-scratching truly begins. In a tonal turnaround, Black Bear becomes a film about the making of a film, and this is where Levine’s screenplay truly finds its bearing and begins to hold the self-aware bite necessary.

In an opening that’s more Cassavetes than Kaufman, moments of dark comedy and tension are accompanied nicely by Giulio Carmassi and Bryan Scary’s score – which couldn’t be more Bernard Herrmann if it tried. Playing with the audiences’ expectations in an auditory sleight of hand, the grating tension and bizarre tone is only heightened by hints of the shrieking violins of Psycho (1960) which permeate the picture.

The further down meta-lane the film journeys, the quicker the rhythm builds. Personas begin to change and there is rarely a minute of true certainty throughout. Despite some moments offering more confusion than catharsis, it is the fast-paced beats of the film that maintain the arresting intensity and intrigue that makes the film so engaging. Central themes invite discussion of the morals of toxic director-actor relationships and the lengths people go to pursue their artful desires. Although, at times it begins to bear a little thin, there is enough self-awareness and ingenuity in the dialogue for the Lynchian style to shine through.

Complimenting this is the stellar Aubrey Plaza. In her best performance yet, she grounds the story’s surreal centre. Known for her dead pan delivery and sarcastic characters (Parks and Recreation, Ingrid Goes West) – this film is a platform for the other side of her acting ability, and from this she shines. Despite the mesmerising nature of the films enticing illusions, it is Plaza’s performance that sticks in the mind, often anchoring some of the more horrifying scenes throughout. It’s not quite a ‘Bear Witch Project’ but in moments that border on mockumentary, there is wonderful intensity and engaging psychoticism to her performance.

Although a puzzle of a film, the central themes and intentions of the director remain evident throughout. Discussions of difficult directors and provocative actors beam through with a self-awareness that ever so slightly veers into smugness. Possessing a bizarre combination of the slapstick silliness of Noises Off… (1992) and the surreal intensity of Mulholland Drive (2001) – it is fair to say that the enchantment of Black Bear stems from the mystery box of its narrative.

It seems Black Bear is destined to polarise audiences. But, Levine would want nothing more from his intentionally sardonic sneer at the complexities of filmmaking and the blurred the lines between life and art. Although, at times, it does seem as though the film pulls the rug from under the audience before they even know it’s there – there is no denying the strength of the central performances and the engrossing confusion of the films second act.