Whether this genre is wrapped in a superhero adventure, lovers on the run road-movie, fantastical teenage flick, or decade spanning saga, each has an equally impactful ability to push the emotional buttons of youth.

Coming-of-age films tend to be varied tales of growth and development, capturing close-to-home truths and human experiences. Films that fall under this genre often unite in their ability to appeal to the emotional side of adolescence. Even big-budget blockbusters, such as Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018), hold their affecting weight in an individual facing conflict or coming to a profound realisation. We can’t relate to the experience of being bitten by a radioactive spider, but we can connect to the terrifying nature of dealing with maturity – and of course, the great power and great responsibility that comes with this. It seems appropriate that at the heart of one of the world’s biggest franchises is the story of a teenager evolving and dealing with bigger things.

Other hero centered tales – possibly The Incredibles (2004) or Big Hero 6 (2014) – have multiple threads of storytelling focused upon progression and change. In fact, developing as a person lies at the heart of the majority of standard American blockbusters. Within the standard, act-based structure of our big-screen adventures, our central figures must meet a conflict and overcome it. Whether that’s Miles Morales adapting to his newfound powers, or Dash and Violet understanding the importance of family, character growth is an ingrained expectancy of a lot of our wildest movie adventures.

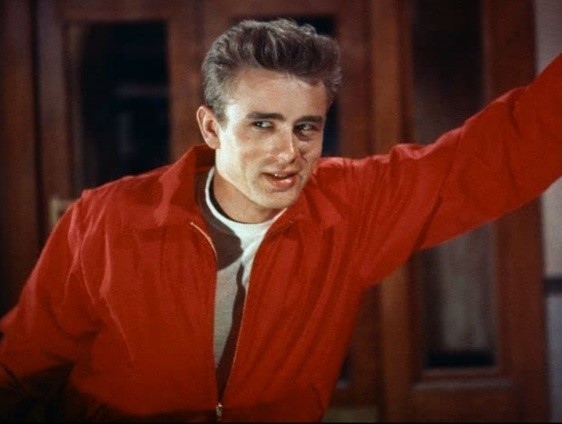

Tracking the history of this genre, in many ways, is a tragic one. James Dean is an icon of American cinema, cemented by his roguish image in Rebel Without a Cause (1955). His iconic image remains an unbelievable fact considering his death at 25, just before the release of this film, which exudes the quintessential style of rebellious American culture. The many coming-of-age themes in Rebel Without a Cause left an indelible impression on the shape and structure of our best-loved tales of change.

James Deans’ feature sees our protagonist relocate to a new town, a recurring coming-of-age concept. My Neighbour Totoro (1988) opens with two young girls moving to a new home, and is often cited as a coming-of-age tale in reverse. While Lee Daniels’ Precious (2009) centres on a teen who enrolls in an alternative school, hoping her life can change for the better. Moving on and tackling new environments is central to many of our favourite Pixar adventures- cue the stirring poignancy of the Toy Story films (1995-2019) or an extraordinary journey through the Land of the Dead in Coco (2017).

James Deans’ role as a troubled teen in Rebel Without a Cause has become another common coming-of-age criteria. Angsty teenage icons can be sourced in delightfully exaggerated form in Winona Ryder and Christian Slaters serial killer sweethearts in Heathers (1988) – who also take guidance from the equally iconic lovers on the run in Fritz Lang’s You Only Live Once (1937), Goddard’s Pierrot le Fou (1965) or Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (1967).

All of these films possess anti-hero elements, and at the top of this ‘pyramid of geezers’ is James Deans’ iconic figure of fashion. It’s hard to watch Dazed and Confused (1993) and not draw comparisons to a character aesthetic of the archetypal ‘too cool for school’ American teenager. Sometimes all that coming-of-age needs to do is capture a feeling and a mood of youth, and it is Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused that seems to be the most obvious example of this. Linklater’s film could be seen a spiritual successor to George Lucas’s American Graffiti (1973), a 60s set feature which lacks the oozing coolness of Dazed and Confused. But, it more than makes up for this with it’s intoxicating charm and cartoonish depiction of an innocuous age of naivety, packed full of coming-of-age themes and a soundtrack as innocent as the culture it depicts.

Effectively, the coming-of-age drama is its own sub-genre of the teen film. Sadly, adolescent-centered stories are frequently dismissed as silly and for a specific audience. Frustrated stereotypes of serviceable school-based stories of angst and broken hearts was joked at in Not Another Teen Movie (2001), but it seemed that Joel Gallen’s film missed the point. There will always be an audience for these types of films because its something we’ve all experienced. Our hearts can’t help but attach to the different character quirks of the group in The Breakfast Club (1985). Played by Molly Ringwald, one of these is the naïve girl attempting to act above her age. Incidentally, Ringwald had a brief cameo in Not Another Teen Movie, this time playing the wise adult who knows more than the kids. This funny appearance also captured the continuing attachment to our teenage years that can make these movies so appealing.

Expressing our attachment to youth through a universal depiction of teenage life is an almost impossible task considering the diverse nature of adolescent experience. Greta Gerwig’s debut feature Ladybird (2017) makes an excellent effort to highlight the perils of a teenage girl’s life. However, it was the earnest attraction of Saoirse Ronan’s performance and her sublime chemistry with her on-screen mother, played by Laurie Metcalf, which anchored this. It could be argued that Marielle Heller’s The Diary of a Teenage Girl (2015) did a better job. This 70s set feature covered harsher realities despite it’s often surrealistic aesthetic. Other mainstream hits like Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight (2016) highlighted similar themes within a different setting. The line “at some point you’ve got to decide for yourself who you gonna be” summarises everything that coming-of-age is supposed to be about.

Other LGBTQ+ stories have been the focus of capturing the emotional weight of the transition from teenager to adulthood. These diverse tales have included passionate summers in idyllic Italian settings (Call Me By Your Name, 2017), Shakespearian surrealism on the streets of Portland (My Own Private Idaho, 1991), or whirlwind high-school romances (Blue is the Warmest Colour, 2013). All of these films hold a unique setting and style, but, a common coming-of-age ground is met, which ultimately hits the same emotional chord.

Contrastingly, some of the best coming-of-age films take place in the comedic world of teenage cinema. As iconic as it gets, the excessively 80s Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986) is a quotable teenage fantasy. Matthew Broderick’s central slacker is a further example of the go to design of loveable troublemaker characters. While Alan Ruck’s character is the ultimate coming-of-age figure, who changes dramatically all within one day of fun. In slightly less wholesome fashion, American Pie (1999) journeyed through the explicit vision of 90s high-school America. Directors Chris and Paul Weitz topped this effort with an utterly charming feature, About a Boy (2002), which reverses the standard coming-of-age tropes, with a young boy teaching a grown man how to face and embrace the world around him. Still, it is the American high-school experience that seems to be the most suitable place to capture the perils of adolescence. The wonderful Juno (2007) is a sweet comedy-drama mash-up, while The Perks of Being a Wallflower (2012) is a funny and painfully moving film which may be one of the perfect examples of coming-of-age on screen.

Although high-school locker rooms and crowded cafeterias are where youthful dramatization can be most obviously sourced, it isn’t just American films that capture coming-of-age concepts. Central to François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959) or Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy (1955-1959) are themes of maturing and attempting to understand the world around you. And, from art-house to all-out indie, Shane Meadows’ This is England (2007-2015) tracks a uniquely grounded insight into the evolution of youth through the eyes of our protagonist Shaun (Thomas Turgoose).

In a similarly expansive saga, it could be argued that no film got to the heart of getting older more effectively than the time-spanning life captured in Richard Linklater’s Boyhood (2014) – possibly the most authentic depiction of progression since it was filmed across a period of 12 years. Depicting the real-time evolution of a boy played by Ellar Coltrane, this one sometimes feels more documentary than drama, and is all the more affective for that reason.

Whether this genre is wrapped in a superhero adventure, lovers on the run road-movie, fantastical teenage flick or decade spanning saga – each has an equally impactful ability to push the emotional buttons of youth. It doesn’t matter if we are connecting to tales of awkward teens finding their place in a confusing social structure or to stories of trendy rebellious teens. There is often a central uplifting notion to the coming-of-age which argues that despite its transience, adolescence is, in some ways, an ever-lasting experience. And, perhaps the biggest attraction to these stories is the joyous uplifting ability they can have, with most of them arguing that despite the conflict or difficulty of the journey, in the end, it’s all going to be “alright, alright, alright.”