Calling Parliament back from recess on a Saturday (after it was called away for the Easter break) would no doubt always be headline news, yet this was to save a crucial British Steel plant in Scunthorpe. With the Government now in control of the site, this has been a political headache for them, and a financial one for the taxpayer.

Government assets shaped up, set for the private market, was Margaret Thatcher’s fever dream. Her worst nightmare would have been to see the Government stepping in to save a loss-making firm, a reincarnation of one that her government privatised back in 1988.

So what has happened, why is it such big news, and how does it matter to the North East?

How “British” is British Steel?

The original company known as British Steel folded in 1999, when it merged with a Dutch company, which was later taken over in 2007 by the Indian firm Tata Steel. After the 2008 financial crisis, Tata’s UK arm made heavy losses, and in 2016, private investment firm Greybull Capital bought the Scunthorpe plant to revive the British Steel brand.

After Greybull surrendered the plant to the Government insolvency service in 2019, Chinese firm Jingye acquired the firm the next year for £70 million, promising £1.2 billion of investment.

Jingye says that the plant loses £700,000 a day. In December last year, talks between them and the government over Scunthorpe’s steelworks broke down, with the government considering nationalising the brand as a last-ditch rescue attempt.

That would necessitate the taxpayer funding a firm making heavy losses, the antithesis to what the mass privatisation of the 1980s was intended to bring about.

What’s the rush?

The plant in Scunthorpe employs 2,700 people and is the only UK plant capable of making virgin steel, a stronger type made by melting down iron ore in a blast furnace.

It’s extremely carbon-intensive, and steel bosses suggest it is possible to make them in an electric arc furnace (EAF for short). However, the UK has one of the world’s lowest percentages for using EAFs, as our technology has not caught up yet.

Jingye says the blast furnaces are no longer sustainable – lower-carbon production promised by the Chinese firm when they bought British Steel in 2020 has proved financially challenging, with The Sunday Times reporting in January 2025 that the highlight – an EAF on Teesside – would no longer go ahead.

Without the Scunthorpe plant, the UK would be the only leading economy in the G7 unable to make virgin steel, which is instrumental in buildings, railways and other key aspects of national infrastructure. Thus, if the Government is serious about its oft-reported focus on growth, it would want to rely on a key part of the quest for infrastructure.

A more time-related imperative is that supplies of raw materials for the sheer heat needed to run blast furnaces are running out – restarting one is a difficult and expensive process. In March, steel frame construction firm and British Steel customer Reidsteel claimed the firm had “already decided to stop ordering raw materials”. British Steel disputed this, yet the prospect of Jingye unilaterally shutting down the plant angered local steelworkers and the Government.

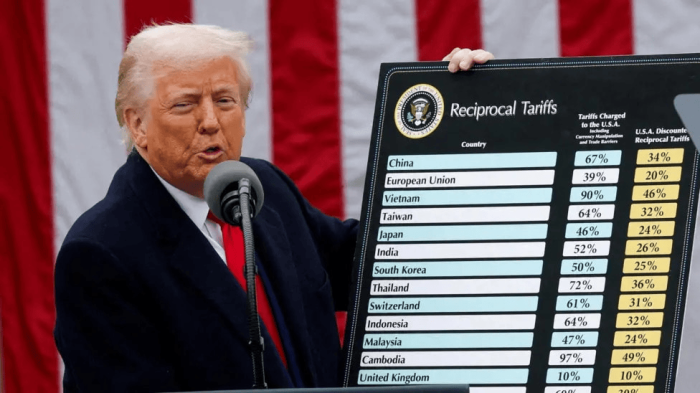

While British steel production is nowhere near the level it once was, it remains a key element of the national infrastructure. The pressures haven’t been helped by Donald Trump’s 25% tariff on imported steel.

What has the Government done now?

Emergency legislation is exactly that – emergency – and rushing a whole new law in a day shows the gravity of the situation.

The new Act does not go as far as full renationalisation: Business Secretary Jonathan Reynolds says it’s a likely next step, and that’s still on the table if Jingye agrees. After Royal Assent – the final seal of approval to take effect – was given at around 6 pm on Saturday evening, officials could now take direct control of the plant.

Direction has been given to British Steel officials to keep the plant open, and responsibility for raw materials lies with Reynolds’ department.

There were worries within Government of local unrest. That, for now seems to have been averted. A large protest through Scunthorpe against Jingye passed on Saturday, and steelworkers at the plant blocked access to the firm’s executives, but that was the limit. Sir Keir Starmer went to meet workers after the law was passed.

The Conservative leader Kemi Badenoch said that the Government had “botched” a deal she had struck with Jingye when the general election was called (though no evidence was forthcoming). Reform UK, meanwhile, went further, with Richard Tice, who visited York earlier this year, calling on Reynolds to “show your cojones”, which won him some ballsy headlines.

What’s it to me?

Put simply, it might decide how much of the legacy of our local industrial history in Yorkshire and the North East can continue. Scunthorpe might be just over the border in Lincolnshire, but what happens here could detrimentally affect British Steel’s other site on Teesside, where the firm scrapped a planned EAF.

After the Chinese takeover, LinkedIn suggests that British Steel has become a good choice for bilingual York graduates. Engineering students from a Chinese background seem to take to the firm, as they have the linguistic and technical know-how to cross both aspects of the company.

This may set up a piece of dissonance: why should the Government even think of taking over a loss-making venture, when it has barely any fiscal headroom? The broader implications of this last-ditch measure may be felt both in and outside Downing Street for some time yet.