Maestro is a film that achieves startling depth in its portrayal of a relationship of contradictions, one that thrives in loving mundanity but is undercut by a lingering, burning, sadness.

It is this focus on contradiction that is at the heart of Bradley Cooper’s latest directorial outing, a biopic of the great composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein, probably best known for composing the score for West Side Story. Cooper’s Bernstein struggles to manage being simultaneously a charming, effervescent performer and a reclusive, tortured creative.

However, the true focus of the film isn’t Bernstein alone, but his marriage to Felicia Montealegre (Carey Mulligan). Mulligan’s performance is perhaps the stronger of the two, a considered portrait of a woman with a deep sadness, who struggles with the conflict between the love they share and Bernstein’s inability to truly meet her emotional needs.

The film refuses to label Bernstein’s sexuality and the level to which the two’s love was romantic, but this doesn’t take away from its genuinely touching portrayal of a supportive and intimate but simultaneously strained and flawed relationship.

The film faced much controversy for Cooper’s use of a prosthetic nose in his portrayal of Bernstein, a Jewish composer. This criticism was well founded, with Cooper’s performance strong enough to render the prosthetic redundant, leaving its problematic nature as its only real impact on the film.

The cinematography of Maestro is stunning, with a fascination with the use of light, especially in its interplay with the thick veil of cigarette smoke that defines the opening acts.

The first half of the film (the early years of Bernstein and Montealegre’s relationship) is shot in black and white and is conscious of itself as a performance, with Cooper and Mulligan briefly breaking into ballet at one point, while the second half becomes much more concerned with gritty reality in a gently sepia tone.

The film opens with a quote from Bernstein himself, ‘A work of art does not answer questions, it provokes them; and its essential meaning is the tension between the contradictory answers’, and Cooper’s performance leaves no shortage of questions, presenting a figure of unbelievable talent, charm, and contradiction – a man who cannot choose between solitary, creative melancholy and bombastic personability and performance.

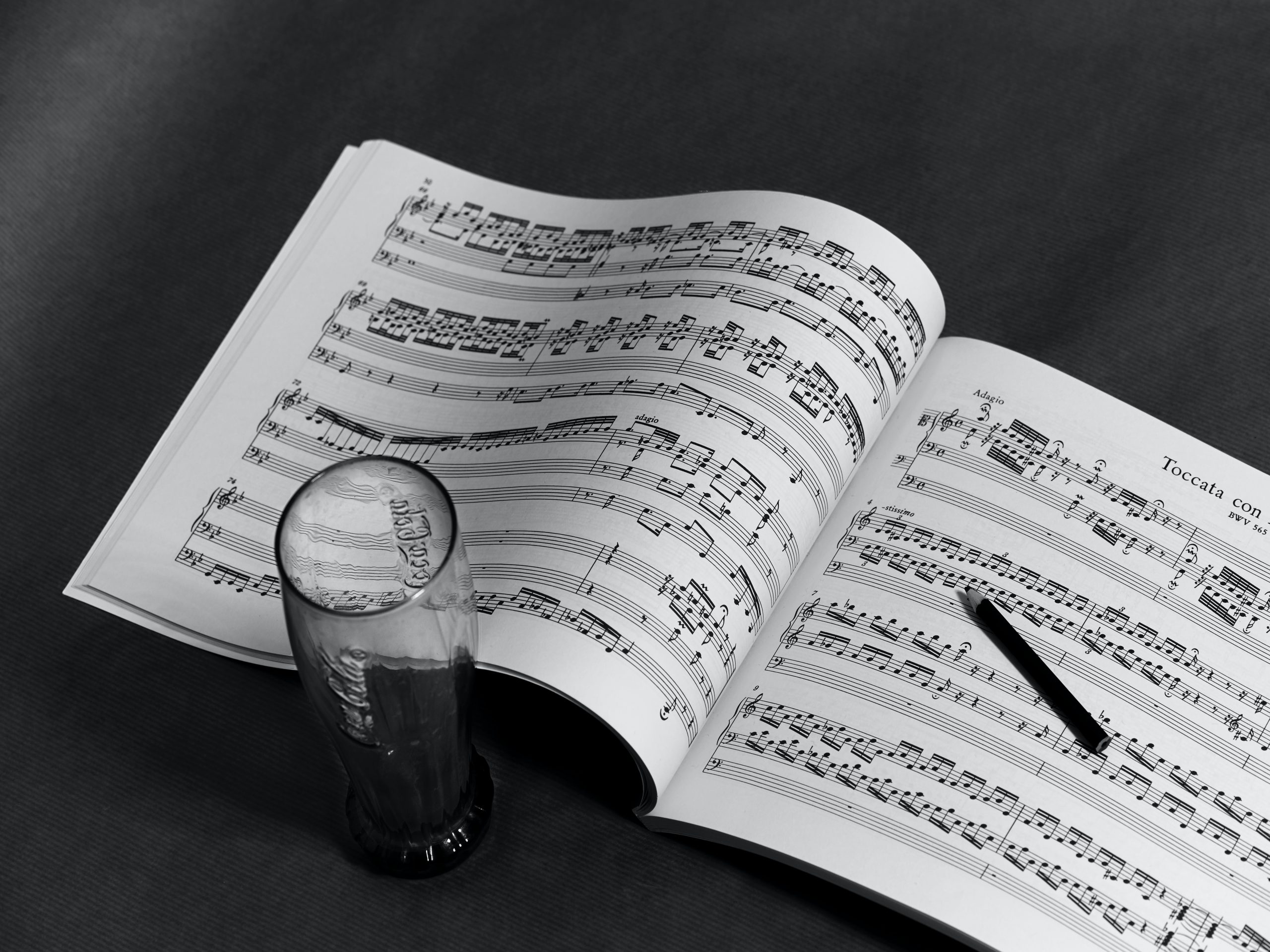

What is clear throughout is that the film is very much a love letter to Bernstein’s career; his music provides a backing to much of the action, but it also breaks through to the fore in extended sequences of Bernstein’s conducting which relish the opportunity to display the unbelievably moving power of his work.

There are also moments that break from this focus on his work though, with tense silence sometimes suddenly breaking through to dominate a scene (and also briefly a bit of Tears for Fears).

Overall, Maestro is a great cinematic and musical success as well as a touching portrait of an immensely complicated relationship. This should come as no surprise given Cooper’s success as director of A Star is Born, as well as its impressive producing calibre, with both Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg involved in production.

However, its slow pacing may frustrate some, and its use of a prosthetic nose was a major misstep. It also makes little effort to walk its audience through what makes Bernstein as great as its characters keep telling them he is, which means its primary audience may be limited to those who are already fans of his work.

Cooper’s film is stunning and thought-provoking, but he has perhaps missed an opportunity to introduce a new generation to a truly great, if complicated, artist.